In this episode of Re/Collecting Chapel Hill, we learn about Elizabeth Cotten, one of Chapel Hill's most beloved musicians. We search for signs f Chapel Hill in Cotten's music and learn about life for a young Black girl in the turn of the century South. Producer Mandella Younge joins Molly as co-host for this episode. Special thanks to Glenn Hinson, Brent Glass, and the Chapel Hill Historical Society.

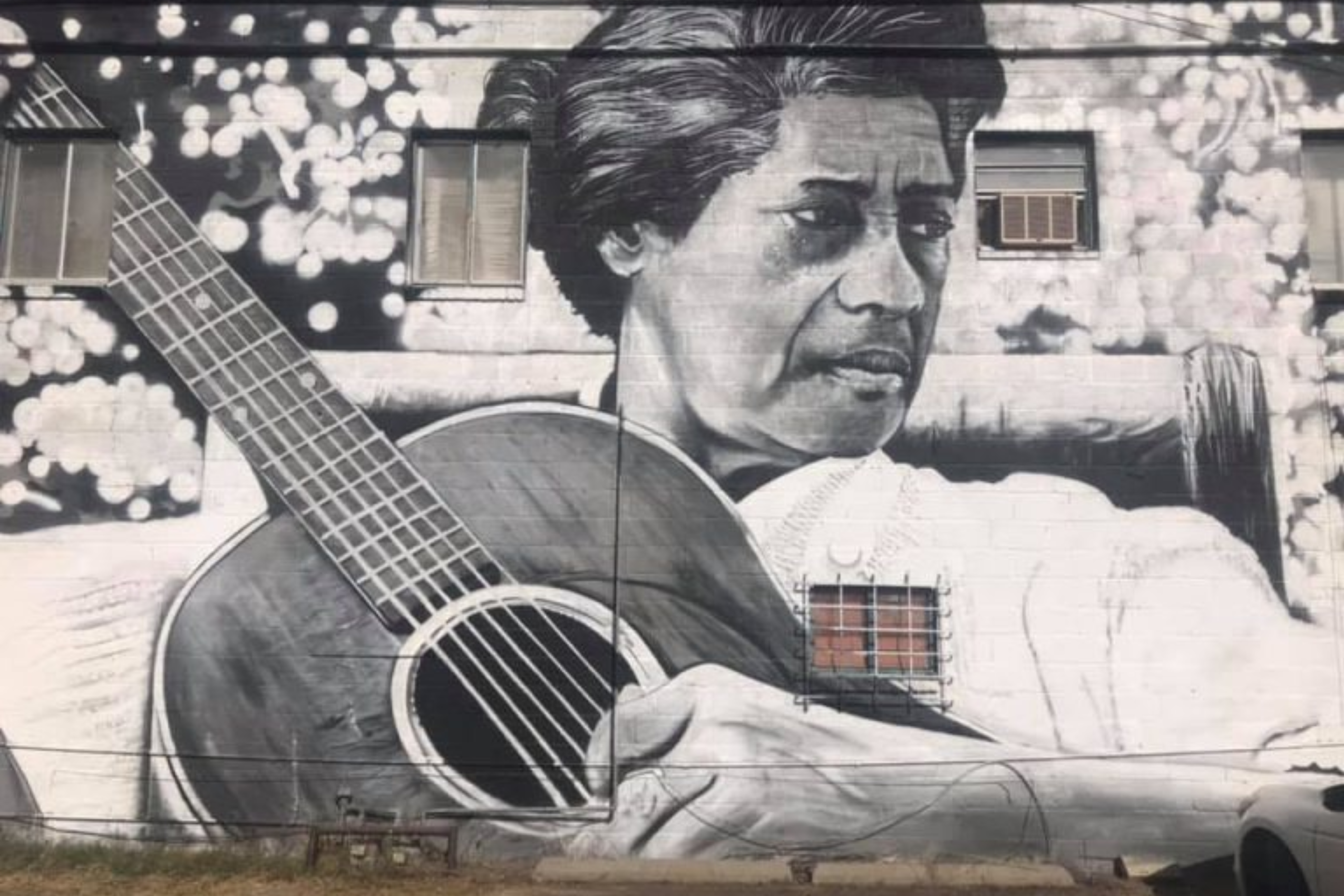

Elizabeth Cotten Mural

By Scott Nurkin

Installed 2020

Located on the 111 N. Merritt Mill Road on the Chapel Hill-Carrboro line.

Episode Links:

- Mike Seeger Collection at UNC Wilson Library -- the collection includes dozens of recordings Seeger made of Elizabeth Cotten, playing, speaking and in concert.

- Good Morning America on Elizabeth Cotten

- 1976 N.C. Bicentennial Folklife Festival Schedule in the Carolina Times -- Ms. Cotten shows up on the lineup several times

- "Black as Folk: The Southern Civil Rights Movement and the Folk Music Revival" - Grace Elizabeth Hale -- painting rural Black southerners as "the folk" in a bid for Northern white sympathies during the Civil Rights Movement. The advantages, limitations, and who it left behind.

- Elizabeth Cotten -- with a great list of sources at the bottom

- John Ullman's liner notes -- for Cotten's posthumously released album, Shake Sugaree

- Extensive liner notes on When I'm Gone were compiled from taped conversations with Elizabeth Cotten, Alice Gerrard, and Mike Seeger between 1966 and 1979.

- Public Art | Chapel Hill Community Arts & Culture — As part of the North Carolina Musicians Mural Project, the Elizabeth Cotten mural honors the local blues legend and her lasting impact on the community.

The true story of Willie & Johnson

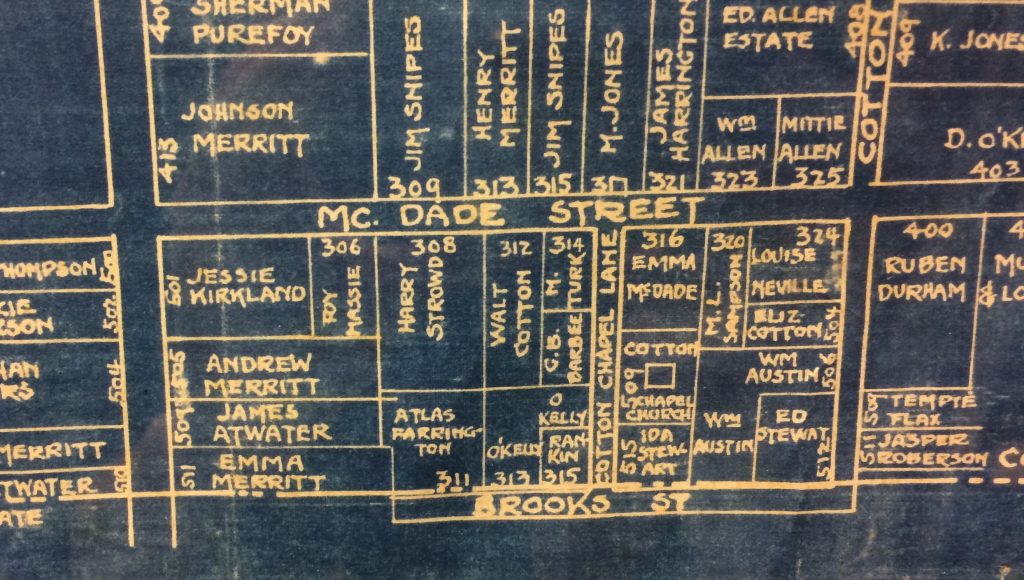

Willie Allen was born in Chapel Hill in 1890, the youngest child of six. His father, Edmond Allen, was a carpenter, and the family lived right across the street from Mrs. Louise Nevilles, Elizabeth Cotten's mother. He was just 15 years old when we has shot and killed by Johnson Merritt in September, 1905.

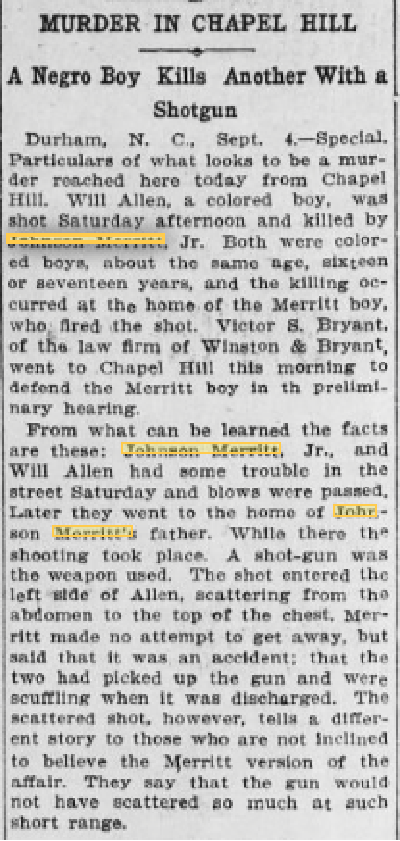

Raleigh Morning Times, September 5, 1905

Johnson Merritt, Jr. was born in 1889, the second child for Johnson and Annie Merritt. His father worked as a "hotel servant" according to the 1900 census.

He was 16 years old when he shot and killed his neighbor and friend, Will Allen. The death was ruled an accident, and Johnson was very quickly released from police custody.

Four years later, Johnson Merritt married Miss Dora Weaver, and the young couple moved into a house on Rosemary Street with their daughter, Dorothy. Johnson Merritt worked as a dormitory janitor and Dora Merritt took in laundry at home. Subsequent years were marked with tragedy: the couple lost two sons in their infancy and by the time Johnson Merritt was in his 40s, he had become a widower. He died in 1954 in West Virginia.

Newspaper accounts of Will Allen's death told a limited story. They often sensationalized the death and overemphasized race.

Raleigh Morning Times, September 5, 1905

Chatham Record (Pittsboro, NC) Sept. 7, 1905

Wilmington's Weekly Star, a white newspaper founded and edited by a white supremacist and confederate, also covered the incident. It played a large role in spreading propaganda which was especially apparent in its coverage of the 1898 Wilmington Massacre less than a decade prior. Read more about the Wilmington Massacre.

View this short article in context to see what other kinds of news stories the paper reported.

The Weekly Star (Wilmington) on Sept 8, 1905.

A few newspapers reported that Johnson Merritt was not charged for Will Allen's death in a short notice like this one in the Statesville Record and Landmark:

Statesville Record and Landmark, Sept.8, 1905